Halachot in the tradition of our Chachamim from Morocco

Dozens of Audio & Video Shiurim by Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar

Hilula of Moroccan Tzadikim

Sefarim based on our Morrocan Minhagim

Monthly Sponsor: Available

Weekly Sponsor: Available

Sponsor of the Day: Available

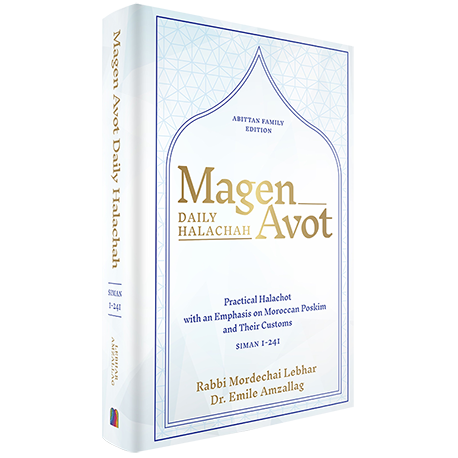

Magen Avot - Daily Halacha

Click here to purchase

Daily Moroccan Halachot

Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar, author Magen Avot

Redacted by Dr. Emile Amzallag

DAILY HALACHOT PODCAST  ON APPLE

ON APPLE  ON SPOTIFY

ON SPOTIFY

Daily Halachot Topics

There is a well-known custom to eat dairy foods on Shavuot. The Rama (Orah Haim 494:3) explains that the source of this custom is in commemoration of the Shtei HaLehem, the two loaves of bread that were specifically offered on Shavuot in the times of the Temple. Just as we have two cooked food on Passover to symbolize the Korban Pesah and the Korban Hagiga, so too on Shavuot we should have a dairy meal and a meat meal to commemorate the two loaves of bread. The Magen Avraham explains that we eat dairy foods because when Bnei Israel received the Torah and learned all the laws of Kashrut, slaughtering and of koshering utensils, they needed to time to prepare meat in a Kosher fashion and in the meantime they could only consume dairy foods. Yet another explanation is that Torah, which we received on Shavuot is compared to milk as it written in: “Devash veHalav Tahat Leshonech” (Shir HaShirim 4:11). The Gemara (Kiddushin 34a) explains that women are exempt from positive Mitzvot that are time-bound and are obligated in Mitzvot that are not time-bound. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 106:1) writes that prayer is not a time-bound Mitzvah and therefore women are obligated to pray. Although it is true that in its current form prayer is bound by specific times, such as Shaharit only being able to be recited at certain times, the Torah only requires one to simply pray once a day. In other words, on a Biblical level, one must only recite some sort of personal prayer sometime throughout the day and one will have fulfilled one’s obligation. The Sages eventually instituted a standardized text of prayer and the obligation to pray three times a day, at certain times. The Magen Avraham (96:2), citing the Rambam (Tefila 1:1,2), says that women would fulfill this obligation as long as they recited any sort of personal prayer at some point during the day. The Ramban, however, says that the obligation to pray is Rabbinic in origin and therefore women would be exempt. The practical ramification of this dispute does not involve whether a woman must pray, since the Halacha follows the Rambam, but rather what prayer must be recited. Unlike the Magen Avraham, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer vol. VI, § 17) says that when a woman prays, she should specifically recite the established Amida since it incorporates praises, personal requests and thanks to Hashem. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 7, § 25) and Rabbi Pesach Eliyahu Falk (Mahze Eliyahu, § 19:9) write that women may recite any type of personal prayer, but they must do so twice a day. According to this opinion, if a woman is able to recite the Amida, it should be specifically Shaharit and Minha, since Arvit is considered more of a voluntary prayer. If a woman is able to set aside time to recite two prayers a day, it is certainly praiseworthy. Furthermore, if a woman prays Shaharit, she should ideally also recite the blessings before and after the the Shema as well as the Shema itself. Although the Shema is a time-bound Mitzvah, there is an opinion that the blessings of the Shema should not be recited with Hashem’s Name. Nevertheless, since there is also an aspect of praise in these blessings, a woman may recite them with Hashem’s Name. Summary: Women are obligated in prayer at least once a day, but should try to pray twice a day if possible. Women should recite the established prayer rather than a personal supplication. Based on the Gemara (Berachot 31b), the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 102:1-4) rules that one may not sit or pass by within four Amot (roughly 6 feet) of one who is reciting the Amida. Regarding passing by, the Elya Rabba writes that it is not permitted because such an act will distract the one who is reciting the Amida. The Haye Adam, however, says that the reason is that the Shechina-Hashem’s Presence-surrounds the one praying the Amida and walking by the Shechina would be improper. The practical difference between these two opinions involves a Halachically-valid Mehitza. A Mehitza is a partition which has implications for Shabbat, a Sukkah, etc., and measures ten Tefahim high and four Tefahim wide. (It should be noted that in the context of this Halacha, Mehitza does not refer to a partition that is used to separate men and women during prayer.) This Mehitza can be anything from a chair, to a table or the like. According to the Haye Adam, such a Mehitza will be effective to create a partition between the one praying and the Shechina, and therefore one would be able to walk by even within four Amot. According to the Eya Rabba, on the other hand, a Halachic Mehitza is not effective in preventing a passerby within four Amot from distracting the one praying and thus one would not be able to walk by. Only some sort of partition that is taller than the one praying would be satisfy both opinions. Rabbi Yaakov Hagiz (originary of Fes, who later became well known in Jerusalem in the 1600’s) in his monumental work Hilchot Ketanot, (vol. I, § 4), concurs with the Elya Rabba and says that a Halachically-valid partition is not sufficient to prevent a passerby within four Amot from distracting one who is praying. Another practical application is in a circumstance when one prays at the entrance way of a synagogue. On one hand, one is not permitted to pass by one who is in the middle of the Amida, but on the other hand, if one cannot pass, one will not be able to enter the synagogue until the person praying finishes. Rabbi Avraham Buchach (Eshel Avraham) and Rabbi Shalom Schwadron (Da’at Torah) write that a person does not have the permission to render a public passageway off-limits to other congregants by standing there for the Amida. As such, they and others, such as Rabbi Eliezer Waldenburg (Tzitz Eliezer, vol. IX, § 8) write that in such a case, it is permissible to walk within four Amot by someone who is praying so that one can get into or around the synagogue. Although there are circumstances when one may be lenient regarding where one prays or where whom one passes by, in general one should be careful to to afford others the proper room to pray. Summary: One may not sit or walk within four Amot by one who is reciting the Amida The Shulchan Aruch (O.H. 101:4), basing himself on the Rosh (Berachot, ch. 2), writes that one may pray in any language that one understands. Rabbi Baruch Toledano (Kitzur Shulhan Aruch, 90:6) writes that women and people that did not know Hebrew could pray in Arabic or any other language they knew. On the other hand, the Hatam Sofer (§ 84) comments that the Shulchan Aruch’s intention is that one may do so on an intermittent basis, not consistently, and that it is inappropriate to recite the entire prayer in a foreign language. Historically speaking, the Hatam Sofer’s opinion was also in response to the Reform movement, who sought to translate the prayer into German and also to remove any references to Zion. In previous generations, the Hebrew language was understood mostly by a scholarly elite and therefore the prayer was not easily accessible to all. Nowadays, however, Hebrew reading and comprehension are immeasurably more accessible to the average person. Furthermore, there is a wealth of translated and transliterated Siddurim available such that praying in Hebrew is much easier. Siddurim nowadays are, for the most part, punctuated with Nekudot, which also makes reading even easier than non-punctuated text. Additionally, the Kaf HaHaim (K.H., O.H. 101:16) says that the Hebrew language is replete with Kabbalistic power that cannot be mimicked by another language. Thus, although permitted according to the letter of the law, it is inappropriate for one who is not yet literate in Hebrew to remain so long term and to pray in one’s native language. That being said, there are circumstances in which one cannot at the moment pray in Hebrew, such as a convert or a Ba’al Teshuva. In such a case, one should pray in whatever language one knows rather than skip the prayer altogether. Certainly, part of such a person’s Jewish learning should include mastery of the Hebrew language. It should be noted that this Halach applies in the strictest sense to the Amida and the established prayers that accompany it. Regarding different supplications, Piyutim and the like, the Kaf HaHaim (ibid:17) says that there is much more leniency in reciting them in different languages. Examples of these include the Bendigamos hymn before Birkat Hamazon that is recited by Spanish Jewry or En Kelokenu that is sung in Arabic by Moroccan Jews. Summary: Strictly speaking, one may pray in any language. Practically speaking, however, one should only do so if circumstances necessitate it and should strive to learn and pray in Hebrew. Portions that are not central to the prayer may be recited in different languages. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 99:1) says that if one drank a Revi’it (about 86 mL) of wine one may not pray until the effects of the wine subside. If one drank greater than a Revi’it and can maintain the composure needed to speak before a king, then if one prayed, one would fulfil one’s obligation to pray. If one drank to the point where one would not be able to maintain the proper composure, one’s prayer is considered an abomination and if one prayed one would need to repeat the prayer when the effects of the wine subside. The Mishna Berura (M.B., O.H. 99:1) says that this rule also applies to other alcoholic beverages. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch.45, § 28) says that since some alcoholic beverages, such as Arak, have a higher concentration of alcohol than wine, the aforementioned amounts one would be able to drink before praying would be less than a those for wine. The Rama (ibid:3) says that nowadays people are more lenient with regards to drinking since contemporary wines are not as potent as those in the past, and because it is common to pray from a Siddur, which ensures at least a modicum of concentration. Nevertheless, one should know one’s limits and should not pray if one feels intoxicated. The Kaf HaHaim (K.H., O.H. 99:5) cites an opinion that if one is intoxicated, one should not pray even if one will miss the the time for prayer. Rabbi Baruch Toledano questions the practice in Morocco to drink alcohol while eating and then pray Minha. Citing the Rama, he says that alcoholic beverages these days are milder than before and everyone is accustomed to using a Siddur, and therefore the practice is permitted. It goes without saying that this only refers to a case when the congregants are able to maintain the requisite composure and focus. Summary: If one drank alcohol one may not pray until the effects of the alcohol have subsided. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 95-1-3) discusses the proper composure that one must have while praying the Amida. One should place both of one’s feet together, bow down one’s head so that one is looking towards and imagine that one is in the Bet Hamikdash with one’s heart directed to the heavens. Furthermore, the Mishna Berura (M.B., O.H 95:5) states that whoever prays without closing one’s eyes does not merit to see Hashem’s Countenance when one passes away. If one must keep one’s eyes open in order to read from a Siddur it is also acceptable. Rabbi Baruch Toledano (Kitzur Shuhan Aruch, § 95), quoting the Zohar, says that one should sway one’s body back and forth while praying and this is based on the verse (Tehillim 35:10) “Kal Atzmotai Tomarna Hashem Mi Kamocha” (lit. “All my bones shall say, ‘Oh Hashem, who is like You?’”) . He cites another opinion (ibid, § 102) that this verse only applies to when one is learning Torah and therefore during the prayer, one should remain still. Both options are viable as long as one is not moving in an exaggerated fashion or one’s eyes are not wandering all about. Additionally, the Shuhan Aruch (O.H. 96:1) rules that one may hold anything in one’s hands since it may detract from one’s focus. Nevertheless, one may hold a Siddur since it aids in in praying correctly and with proper concentration (ibid:2). Nowadays, it is possible to access the text of the prayer on one’s smartphone. Nonetheless, this cannot be compared to a Siddur since it has much more potential for distraction and also does not have the inherent holiness of a Siddur. Thus, one should not use a smartphone during the Amida. If one has no other choice, such as if one is traveling and has no access to a Siddur, one should put the phone on airplane mode so as to block the amount of notifications and other distractions. Since a smartphone that is not on airplane mode has a higher risk of distraction, it cannot be compared to a Siddur and therefore one would not be able to recite the Amida from it. During the other parts of the prayer one could use one’s smartphone, but even then, it would be praiseworthy to have it on airplane mode. Summary: One should maintain proper composure during the Amida. One may not hold anything during the Amida except a Siddur. One may not pray the Amida using a smartphone unless it is on airplane mode.

As the word implies, the Amida must be recited while standing, but there are situations when this is not practical. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 94:4) writes that if by standing to pray one will not have proper concentration, one may sit down to do so. One contemporary example would be if one would were anxious due to the normal jostling of a subway and would concentrate better if one prayed while sitting down. The Shulhan Aruch goes on to say that there is a strict opinion that requires one to stand at least for the first blessing of the Amida and says that one should follow this opinion if it is safe to do so. The Shulhan Aruch (ibid:9) says that if one had to pray sitting down out of necessity, one should repeat the prayer standing up when it becomes possible to do so. Typically, when a prayer needs to be repeated or was missed, one must make a stipulation that if the prayer is truly required then it should count as a prayer, and if it is not truly required then it should be considered as a voluntary prayer. Interestingly, in this case the Shulhan Aruch says that one need not make the stipulation. In other words, standing up for a prayer is so important that one should repeat is as though one did not pray at all. Nevertheless, the HIDA (Birke Yosef, § 94:5) and Rabbi Yehuda Ayash (Matte Yehuda, § 94) write that the custom is not like the Shulhan Aruch and one need not repeat one’s prayer. Rabbi Baruch Toledano (Kitzur Shulhan Aruch), quoting the Kaf HaHaim (O.H. 94), and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer, vol. III, § 9) concur. Rabbi David Yosef (Halacha Berura, Otzrot Haim, pg. 50), based on a modified ruling by his father Rav Ovadia, and Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 45, § 26) both write that one should repeat one’s prayer and make a stipulation. Nonetheless, it appears that practically speaking, the custom is to be lenient and not repeat the Amida. Summary: In extenuating circumstances, one may sit down to recite the Amida. In such a case, one need not repeat the Amida while standing up. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 94:1) rules that when one prays the Amida, one should face the direction of Jerusalem. Most diaspora communities tended to be west of Israel and therefore the direction of prayer would be toward the east. Rabbi Mordechai Birkat Erev (pg. 107) cites a disagreement between Rabbi Ya’akov Emden (Mor Uktzia, § 94) and Rabbi Mordechai Jaffe (Levush, § 94) regarding synagogues which are not located to the west of Israel but rather to the north, or the like. The former says expresses wonder at how the Hechal of many synagogues in countries to the north of Israel are still placed on the eastern side of the synagogue. The Levush, on the other hand, says that since there is a concept that Hashem’s Presence is found in the east, the common practice is to place the Hechal and to pray towards the east, regardless of where in the world one is. In many instances a synagogue cannot be designed such that the Hechal is exactly in the east, either for architectural reasons or due to the orientation of the plot of land. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 45, § 25) writes that if one is in a synagogue in which the Hechal is not exactly to the east, one may pray in the direction of the Hechal, as long as it is roughly to the east and one would not have to turn one’s back to the Hechal in order to pray in a mostly-eastern direction. Similarly, the Hatam Sofer (O.H., § 19) says that when designing a synagogue, the Hechal may be placed such that it is not exactly to the east in order to gain more space for the sanctuary, but that it should still be roughly to the east. Rabbi Haim Ozer Grodzinski (Shu”t Ahiezer, vol. III, § 79), however, says that one may not build a synagogue in any other direction except towards the east. It seems that there is more leniency, even among those with the approach of the Ahiezer, to place the Hechal towards the southeast, if needed, since practically speaking, that is the direction of Israel for communities in North America and Europe. If one is on a plane, Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (ibid.) says that one should estimate where east is, based on the direction of the flight. For example, if one is flying from Tel Aviv to New York, one should pray roughly towards the back of the plane. If one is flying from Miami to New York, one would pray towards to the right side of the plane. [The propriety of standing in order to pray while on a flight will be discussed elsewhere]. Summary: The Hechal should be positioned at the very least in a roughly eastern position in the sanctuary. On a plane one should estimate where the east is based on the direction of the flight. The seder plate (Qe’ara or in Arabic “Sinya dBibhilou”) is set up after noon before the Hag; there is also a custom to set it up closer to the actual seder.[1] The tradition is to do so according to the opinion of the Arizal, with the salt water/vinegar not on the plate itself. In the middle of the plate is the maror. Directly on top is the zero’a (shank bone), and continuing clockwise is the haroset, hazeret (lettuce), karpas (celery), and besa (egg). Resting on top of all this are the three masot.[2] When the seder falls on Shabat, the minhag is to not say Shalom ‘Alekhem. Rather, the first step, Qadesh, is commenced immediately with “Yom HaShishi.”[7] The common practice is that everyone at the table participates in reading the Hagada. Each person reads a paragraph word by word in a special tune with everyone saying the last sentence of each paragraph together.[11] Although the general practice in Morocco was that women would not lean, nowadays, there are reasons to say that circumstances have changed and it is worthy for women to be strict and lean when eating or drinking the different required foods of the seder.[13] The custom for Qidush is that the entire family stands, each with their own cup of wine in their hands. The father (or whomever is leading) makes Qidush with everyone responding “Barukh Hu Ubarukh Shemo” during the berakha.[14] When the father arrives at “asher bahar banu mikol ‘am” all those at the table recite it aloud with him until the ending berakha. Then the father alone says the blessings and everyone answers Amen, sits, and drinks the Qidush (first cup) while leaning (in Arabic “mrtba”) to the left.[15] In some places only the father of the family would perform the washing for the karpas (“krafs” in Arabic).[16] At the point in the seder when the middle masa is broken in two (yahas), it is customary to say a short paragraph in Arabic as follows:[19] Before the passage “Ha lahma ‘anya” at the beginning of the hagada, Moroccan Jews, as well as some Tunisians, Algerians, and Yemenites, have the minhag to take the qe’ara and wave it over the heads of each person at the table, starting with the ba’al habayit (normally the father), and then everyone else descending from eldest to youngest. The qe’ara is waved three times over each person’s head followed by a soft bump. This is done while reciting in a special tune: “Bibhilu yasanu mi-misrayim, ha lahma ‘anya, bené horin” – “With haste we left Egypt, this is poor bread, [now] we are free.”[22] As the Qe’ara is passed over the heads of everyone, one should have in mind that it should serve to bring berakha upon everybody for the indicated reasons. When the Ten Plagues and Ribi Yehuda’s acronyms for them (“desakh ‘adash be’akhab” and “dam vaésh vetimrot ‘ashan”) are said in the hagada, some wine from the cup of the youngest person at the table is spilled into a bowl after mentioning each one,[28] along with a simultaneous pour of water from another cup.[29] The remaining wine and water in the cups is poured into the receptacle into which the drops were spilled and the cups washed out. Haroset is the sweet fruit and nut preparation, eaten with masa and bitter herbs (romaine lettuce), which serves as a reminder of the brick mortar that Bené Yisrael made as slaves in Egypt. Sefaradim universally use Romaine lettuce (hasa, in Arabic l’ksas) as maror.[31] In the city of Dra’a a different green was used called “Leshan Tor;” if this was not available then Romaine lettuce was used.[32] When the father, or head of the seder, arrives at the paragraph of “masa” he raises it and asks aloud, “‘Al shum ma?” – “Because of what is this?” Those at the table answer him with the response written in the hagada. Similarly, this is done for Pesah and Maror, but for Pesah the zero’a (shank bone) is not raised nor touched; rather it is pointed to.[34] On the seder night one is required to eat specific amounts of masa and maror, namely a total of five kezetim of masa and one kezayit of maror. In some places they would wrap the Afiqomen with a napkin, put it on their backs, and walk around the room saying aloud “Kakha yaséu Yisrael mimisrayim, mish-arotam serurot besimlotam ‘al shikhmam, ubné Yisrael ‘asu khidbar Moshé” – “This is how Bené Yisrael left Egypt: with their bags packed and clothes on their shoulders, and Bené Yisrael did so according to the word of Moshé.”[41] [1] Some set up the qe’ara earlier so that once everyone arrives home from the synagogue after ‘Arbit they will not be bothered by having to set it up then. The other reason is that one might have forgotten something and if this realization occurs around noon, one will have time to obtain everything needed. The reason for someone to set it up closer to the seder is only if they know that they have everything needed so at this time they will bring the children to help and spark their interest. See Osrot HaMaghreb (Pesah) and Ribi Abraham Hafuta s”t.[2] The arrangement of the qe’ara is based on Qabala with each component set specifically to parallel the sefirot (spiritual spheres: hokhma, bina, da’at, etc.); anything additional would be detrimental. See Netibot HaMa’arab2 (p.177), QS”A Toledano (Siman 421:16), and Kos Eliyahu (p.18).[3]. This is done to strengthen one’s faith by drawing the following comparison: Just like in the days when the Jews came out of Egypt and merited seeing that redemption, so too will they see the redemption of Mashiah speedily in our days, as this redemption will be heralded by Eliyahu HaNabi, zakhur letob. See Hoq Ya’aqob (480:7:7)[4]Yalqut Shemesh (p.107) records that Ribi Shalom Messas did not have this custom because there is no basis for it in Shulhan ‘Arukh and is originally an Ashkenazi minhag as Keter Shem Tob (Heleq 3, p.80) writes.[5] It is written in Shir HaShirim (2:2) “Keshoshana ben hahohim ken ra’yati ben habanot” (“Like a rose maintaining its beauty amongst the thorns, so too does My faithful beloved among the nations”). Hazal explain that Yisrael amongst the Egyptians reflects this pasuq. To embody it some would place roses on the table during the seder. See Noheg BeHokhma (Pesah §6, p.162) and Osrot HaMaghreb (Pesah).[6]Ner HaMa’arab (p.303) by Ribi Ya’aqob Moshé Toledano (1911).[7] Generally Shalom ‘Alekhem is recited on Friday night in order to greet the two angels that accompany the Ba’al HaBayit home from the synagogue. However, on the night of Pesah, HaShem Himself is present with us and thus no need to greet His servants. Similarly, it is written in the hagada: “Ani velo mal-akh, ani velo Saraf” – “I (God) and not an angel, I (God) and not a Saraf (a type of angel)” when describing who it was that took the Jews out of bondage. See Ben Ish Hai (Rab Pe’alim, Heleq 1, Sod Yesharim).[8] This serves as a remembrance to the white clothing worn by the Kohanim during their service in the Bet HaMiqdash since the seder serves as a remembrance to the Qorban Pesah. It also serves the purpose to make sure that we do not become distracted from this night. The white djelaba also serves as a reminder of the shrouds that were worn by the Jews in Egypt. See Osrot HaMaghreb (Pesah) and Ta’amé HaMinhagim (p.274).[9] The reason for this is in order to ensure that everyone present act like Kings who are free men. The announcement of every step ensures that everyone is concentrated on the hagada. See Bayit HaYehudi (Mo’adim Siman 27:22).[10] This helps the kids to stay awake for the entire seder to hear story of Pesah because children are the main point of the seder, as it says in the pasuq (Shemot 13:8) “Vehigadta lebinkha” – “And you shall tell over [the story of Pesah] to your son.”[11] Through this, people will be aroused to fulfil the misva of telling over the story of leaving Egypt, like halakha states we should. See Qobes Minhagim (Pesah).[12] This is so that everyone sitting will understand and will fulfil the misva of “Sipur yesiat misrayim – Recounting the story of leaving Egypt.”[13] Ribi Yehoshu’a Maman s”t confirms that women would never lean in Morocco. Shulhan ‘Arukh (O”H Siman 472:4) rules that women are not required to lean, and the Moroccan custom is based on this ruling. Rema further explains that the women did not lean based on the ruling of Ra-abia (Ribi Eli’ezer ben Yoel HaLevy ~1200s Vienna). Ribi Mordekhai Lebhar s”t adds another reason being that they were too involved with preparing the seder and would not be present at the table so much. Fortunately, nowadays, all women take part in the seder and thus should also lean. However, if a woman did not lean she does not have to go back and re-eat or re-drink that which she did not lean for, as is required of men.[14] The minhag of saying “Barukh Hu Ubarukh Shemo” is discussed and it is not considered an interruption (hefseq) according to generations of Spanish and Moroccan Sages. See ‘Emeq Yehoshu’a (Heleq 3, Siman 21) and QS”A (p.147).[15] Each person holds their own cup because everyone is obligated to drink four cups. Therefore, the father blesses and everyone stands with their cup ready to drink while leaning.[16] During the rest of the year Moroccans do not wash their hands before eating something dipped into one of the five liquids (among them water). Therefore, the father would wash his hands to invoke the children’s curiosity and prompt their questioning. See Kos Eliyahu by Ribi BenHarosh (p.20), ‘Emeq Yehoshu’a (ibid.), and QS”A (Siman 421:34). Ribi Ya’aqob Benaim s”t (Maghen Abot, O”H p.426 §36) writes that in Tetouan everyone would wash for the karpas. In regards to not washing before eating something dipped in one of the five liquids, see Maghen Abot (p.140) for more detail as this is the ruling of Ribi Shalom Messas (Shemesh Umaghen Heleq 2, Siman 46) and Ribi Yishaq ibn Danan (LeYishaq Reah §9) who attest to this being the ancient Moroccan minhag in line with the opinion of many Rishonim (see Mishna Berura Siman 158:20).[17] The prevalent minhag is not to lean because the karpas comes about only so that the children will ask questions. Therefore, leaning is not required because it is not part of the seder per say, rather, it is an unordinary action done to bring children to ask questions. See Ben Ish Hai (Year 1, Sav §32), Pé Yesharim (p.11) by Ribi Habib bar Eliyahu Toledano of Meknes, Qisur Shulhan ‘Arukh (Siman 421:36) by Ribi Refael Barukh Toledano, and ‘Emeq Yehoshu’a (Heleq 3, Siman 21). See further Maran HaHida in Birké Yosef (§14) who reasons to not lean because the karpas is a sign of slavery, and only those who are free are considered like royalty worthy of leaning while eating.[18] The Hagada Abotenou (p.5) cites this as the opinion of Ribi Refael Bibas of Salé, the grandfather of HaMal-akh Refael Berdugo, as cited by Ribi Abraham Anqaoua in his hagada, Huqat HaPesah (1840). This is also the opinion of the Abudirham and Ma-amar Mordekhai.[19] See the ‘Ereb Pesah Hagada (published in Livorno) as well as the hagadaKo Lehai who writes that the minhag is to say the above and its translation.[20] This piece of masa that is set aside for the Afiqomen is not hidden in the house or “stolen” as is done in some communities. Ribi Yishaq Hazan in his hagadaKo Lehai writes that the reason is so as to not habituate children to steal and act in devious ways.[21] This is done in order to illustrate the story of Yesiat Misrayim for the people at the table causing everyone to fulfill that which is said in the hagada “mish-arotam serorot besimlotam ‘al shikhmam” (“with their bags packed and clothes on their shoulders”), and that which is written (Shemot 12:11) “vekhakha tokhelu oto, motnekhem hagurim na’alekhem beraglekhem umaqelkhem beyedkhem” – “And this is how you shall eat it: your loins girded (prepared to run), your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand.” See ibid., Ta’amé HaMinhagim (p.285), and Ba-er Heteb (Siman 477:1).[22] See the hagada of Rambam (See Mishné Tora, Sefer Zemanim, end of Hilkhot Hames Umasa). The oldest source for the custom is the medieval hagada, Pesah LaDorot by Ribi Yishaq Al-Hadab, which seems to imply that this was customary in many Jewish communities. Ribi Yosef Benaim (Noheg BeHokhma p.163) mentions that Maran HaHida in Ma’agal Tob, observed this custom in Tunisia and Ribi Hayim Palaji (Hayim LeRosh, p.49) writes that it was also customary in Turkey. Ribi Yosef Benaim (ibid.) and Ribi Refael Barukh Toledano (Qisur Shulhan ‘Arukh Siman 421:17) both testify that this indeed was the custom in Morocco as well. There are multiple reasons for this minhag: Question: Can Sepharadim rely on the facts that food products that contain kitniyot derivatives such as corn syrup, corn alcohol, etc.. and no hametz do not need a Kosher for Passover certification? Answer: Sepharadim do not follow the Ashkenaic practice of avoiding kitniyot. (Some Sepharadim refrain from rice and/or chummus). This presents a unique dilemma for Sepharadim who live in North America. As the kashrut agencies are for the most part run by Ashkenazim, many products that contain kitniyot derivatives, such as corn syrup, corn based vinegar, and corn based sugar are not acceptable. This should present no issue for Sepharadim, if so, one could suggest that as long as the item does not contain any trace of wheat in the production, we should be safe to assume that it is Kasher Lepesach. Accordingly, if one would read the label of certain products, such as mayonnaise, and sees that it does not contain any hametz in its ingredients he should assume it’s fine. After further research and discussion with Kashrut experts who are intimately involved with the different ingredients that go into each products, we have discovered that in many products that one would assume has no trace of wheat could very well have traces of hametz and in some instances a substantial amount that would not be nullified before Pesach. The following are based on the findings of Rabbi Avraham Juravel, a world renowned kashrut expert Rabbinic Coordinator for the OU. Due to his vast experience on the field, he was able to give us an insiders view on the potential challenges of relying on ingredients only. Here are a few examples: Corn alcohol, corn vinegar and corn sugar Mayonnaise contains vinegar derived from corn , one would think this does not pose a kashrut concern for Sepharadim as it is merely a derivative of kitniyot, however, corn alcohol, corn vinegar and corn sugar all begin life as corn starch, which is obtained by washing the starch from ground corn. The water in the starch solution is then boiled off until only the powdery starch remains. ADM, America’s largest corn processor, makes cornstarch and wheat starch using the same re circulated water. The corn alcohol that emerges may appear innocent enough on a label, but it is hametz. Similarly, Cargill’s huge dextrose plants in France and Germany, have different buildings house the production of corn dextrose and wheat dextrose, but the same water circulates through both. It’s all hametz. Furthermore, bacteria and beta-amylase, an enzyme, are added to a cornstarch solution to convert the starch to alcohol. But beta-amylase is usually made by soaking barley in water for an extended period. In response to customer inquiries, the company has asserted in writing that the product contains only corn. It is hametz. It is not certain that the amount of wheat absorbed would be batel beshishim. Vinegar White vinegar is made from either wheat or corn alcohol, to which is usually added a starter, typically vinegar from an earlier production. A large U.S. vinegar producer requested Pesach certification for its apple cider vinegar. Hametz vinegars are produced in the same plant, but the company insisted that the apple cider vinegar used a dedicated line and thus was never contaminated by hametz. One prominent Kashrut expert once examined the plant and found that it produces two kinds of apple cider vinegar: regular, which utilizes a starter, and natural, which doesn’t. A single tank in the facility is used to hold starter. At different times this tank contains barley malt vinegar, white vinegar, and “regular” apple cider vinegar. The barley and wheat starters make the starter tank hametz, because kibush davar charif doesn’t require 24 hours to make kavush kemevushal. The starter tank, in turn, makes the regular apple cider vinegar hametz. As a result, even though the cider vinegars have a dedicated line, that line is hametz from the regular cider vinegar that contains starter from the hametz starter tank. Denatured alcohol Denatured alcohol is one to which a denaturant—a foul-tasting chemical—has been added to make it inedible, thereby exempting it from the higher U.S. taxes on potable alcohol. One eligible denaturant is ethyl acetate. Is vinegar manufactured from corn alcohol denatured with ethyl acetate kasher lepesach? Rav Yaakov Blau zt”l ruled that it is not. Most ethyl acetate is made from either hametz alcohol or hametz acetic acid. Although the ratio of alcohol to ethyl acetate is greater than 60:1, because it is specifically made to give taste (avida leta’ama) it’s not batel. Citric acid Citric acid, called lemon acid (humtzat limon) in Israel, is no longer produced from fruit industrially anywhere in the world. It’s made from a sugar like dextrose, which can be derived from corn, wheat, or tapioca. As noted above, corn dextrose is often made with water that was used to boil wheat. Carrageenan Carrageenan, used on Pesach even by Ashkenazim, is made from seaweed cooked in alcohol. Sometimes the alcohol source is barley, as in one major South Korean factory. Therefore, carrageenan needs hashgacha for Pesach, even though there is no alcohol in the final product. These are but a few examples of the complexities in food production nowadays. It is very difficult to assume anything in the Kashrut world based on ingredients without proper supervision. Pesach is a time where our ancestors always strove to never to have any doubt of Hametz in our vicinity. To not purchase food that one is unsure whether it contains Hametz is definitely something we should strive for! Shavuot Halachot Archives:Dairy, Electricity, Cheese

Rabbi Yosef Benaim (Noheg BeHochma, pg. 202) explains that this was not a common practice in Morocco but that there were people who ate dairy foods in Morocco and other Sephardic lands.

A culinary custom on Shavuot that was common in Morocco, however, was eating Matzah. A special dish known in Arabic as Hrabel was made of Matzah meal, sugar and mint. The HIDA (Lev David ch. 31) references the Tola’at Yaakov, who says that Shavuot is likened to Olam Haba (the World to Come) where the body and soul join in a heavenly experience. On Shavuot there was a bread offering, which is symbolic of the physical body, as well as a Minha offering, consisting of unleavened Matzah, which symbolizes the soul. Thus, on Shavuot one eats Matzah to complement the bread offering and to symbolically join the physical and the spiritual worlds. The HIDA gives another reason based on the Zohar that in Egypt, Matzah was the bread of affliction when we were slaves to Pharaoh. On Shavuot, when we accepted Hashem’s Torah, we eat Matzah to symbolize that we are still servants, but to Hashem.

Summary: One may partake of dairy foods on Shavuot but one should also eat meat in honor of Yom Tov. There is a special custom to eat Matzah on Shavuot. Must women pray?

May one walk by someone that is praying?

Praying in a different language

May one pray in another language?

Alcohol before Prayer

May on drink alcohol before praying?

Smartphone as a Siddur

What is the proper composure for prayer?

May one sit for the Amida?

This being said, the importance of standing during the Amida should not be understated. If one has an opportunity to stand, even if it means pulling over and getting out of one’s car, one should not rely on the leniency to sit. Evidently, if it is not safe or there are other factors, one may sitMust one pray towards the East?

Halachot of the Night of the Seder

Preparing for the Seder

Some have the minhag to set out a special cup called “Kos Shel Eliyahu HaNabi” and a place setting for Eliyahu HaNabi z”lé.[3] Most, including Ribi Shalom Messas, do not have this minhag.[4]

Some have the tradition to place roses on the seder table[5] while some put a bowl of live fish on it.[6]The Seder Night

On the seder nights (nicknamed in Arabic “Lilt Lihgada”) men wear a white djelaba (Moroccan tunic) in honour of these special days.[8]

The custom is that the father of the household sits at the head of the table and directs the entire seder to ensure that it is properly conducted. At the beginning of each step of the seder he announces in a loud voice: “Qadesh,” or “Urhas,” etc. Many also have the tradition to sing the steps “Qadesh, Urhas, etc…” stopping at the one they are about to perform. For example, when starting “Magid” they sing “Qadesh, Urhas, Karpas, Yahas, Magid.”[9]

Some have the tradition to encourage the children to participate by saying to them: “Whoever has the strength to stay up until the end of the seder will merit seeing “Shefokh” (the last step of the seder which opens up with the words “Shefokh hamatekha ‘al hagoyim” – “Pour out Your wrath unto the nations…”) and the intent is that the children will get excited and ask “Who is Shefokh a boy or a girl?!” They will then stay up in order to see who “Shefokh” is, when really it is only the last step of the seder.[10]Reading the Hagada

In many families the hagada is read only in Hebrew on the first night. On the second night it is usually read in Hebrew and then translated into Arabic or Spanish. Today, any language that everyone at the table understands must be used in conjunction with Hebrew because the main misva is to understand what is being read.[12]Customs and Traditions of the Seder

a) Leaning

b) Qadesh

c) Karpas (Celery)

The common minhag is that one eats the karpas without leaning;[17] however, some are accustomed to eat it while leaning.[18]d) Yahas

“Hagda qsm l’lah allab’har, ala tnas ltreq, hen kherju jdudna mn masar. Ala yid Sidna oun’Bina, Mussa bn ‘Amram, ‘Ala slam oursa, hen fiqhum ughathum mlkhdma se-iba alhouriya. Hagda yfiqna HaQadosh Barukh Hu, wenomar amen.”

“This is how God split the sea into 12 paths when our ancestors went out of Egypt by the hand of our master and prophet Moshé, son of ‘Amram, may peace be upon him. Just as God redeemed and saved our ancestors from slavery. In this same manner HaQadosh Barukh Hu will take us out [of our current exile], let us say Amen.”

Instead of this last sentence, some say:

“Hagda yfqena min had legalout, wejibna liroushalayim la’aziz ‘alina, lema’an shemo hagadol wehanora.”

“In this same manner we will be taken out of this exile and brought to our beloved Yerushalayim for the sake of His great and awesome Name.”

After breaking the middle masa it is said in Arabic: “Nins bin llmida llmindil, unins ‘lafiqomen – Half between the top and bottom [masot], and [the bigger] half for the Afiqomen.”[20]

In some places, following yahas, the father of the family acts as if he is leaning on a stick, with a package on his back containing the Afiqomen, and those at the table ask him “Me’ayin bata?” – “From where are you coming?” and he responds “Miyose-é misrayim ani, vezé ‘ata baqa’ HaShem et hayam, ubné Yisrael zakhu bekhesef vezahab shel hamisrim, vekevan shelo yakhelu lehitmameha, lo hispiq veseqam lehahmis veyasé-u ‘im ‘ugot masot ki lo hames – I am from the ones who left Egypt and now HaShem has split the sea and Bené Yisrael received the gold and silver of the Egyptians. Since they could not delay any further, their dough did not have enough time to rise, and so they left with masa (unleavened bread) because it did not rise.” Everyone answers him aloud and in a nice tune “veaharé khen yaséu birkhush gadol – and after this they left with great wealth.” Some say “vekhol hamarbé lesaper bisiat misrayim, haré zé meshubah” – “anybody that extensively tells over the story of leaving Egypt is praiseworthy.”[21]e) Bibhilu

Some, specifically those from Marrakech and its surroundings, would do “Bibhilu” with a flowerpot and not the Qe’ara.[23]

Some have the minhag that when a family members is absent on the seder night the Qe’ara is waved over the table itself in their honour.[24] It seems to be that this was done by most people as a special berakha for the house regardless of the family’s presence.

Many wave the Qe’ara over the head of a pregnant woman four times. Already it is done three times over her, and a fourth in honour of the child that she is carrying.[25]

After performing “Bibhilu,” many say together in Arabic: “Hagda kherju jdudna mn masar” (“This is how our forefathers left Egypt”)[26] while others raise and point to the middle masa continuing with the paragraph “Ha lahma ‘anya.”[27]f) Spilling Wine for the Ten Plagues

f) Haroset

The custom is to make haroset using the following ingredients: wine, apples, figs, pomegranates, almonds, and dates.[30]g) Maror

It is important to note that one should be very careful in washing all lettuce, vegetables, and fruits in order to remove any insects that may be on them, especially Romaine lettuce.[33]h) Paragraph of Masa

Many kiss the masa and maror before eating them.[35]

When arriving at the paragraph of “bekhol dor vador” just after masa, everyone sings along until “ga-al Yisrael.”[36]i) Amounts That One is Required to Eat

According to Moroccan posqim, these measurements are determined in volume, not weight[37] and most are of the opinion that the sizes of eggs and olives have not decreased with the passage of time.

However, because it is difficult to properly determine the volume of masa due to air pockets and the like, the minhag of Sefaradim has developed to determine these measurements in weight. Accordingly, a kezayit equals 28 grams, or practically speaking, a half of a circular hand-made masa shemura.[38] Nonetheless, one should weigh the masa and maror prior to the seder in order to ensure that he and everyone at his meal have the necessary provisions to fulfill these Tora prescribed laws. One may even perform this task on Yom Tob, albeit with a non-electric scale, as it is for a misva.

An elderly or sick person is allowed to dip the masa for the misva in water to facilitate consumption.[39]

The proper amount of wine to drink is at least a rebi’it (approximately 3 fluid ounces or 89 mL). Ideally one should drink the entire contents of the cup. However, if one drinks the majority of it he has fulfilled his obligation.[40]j) End of the Hagada

The doors of the house are completely opened when saying the paragraph right before Halel of “Shefokh….”[42]

There is a popular tradition for everyone to read Halel together including “Nishmat kol hai,” in its particular tune.[43] At the end of the seder “Shir HaShirim” is sung.[44]

In Nirsa, the poem “Had Gadya” is sung in Arabic or Spanish along with the Hebrew version.[45]

1) The simplest reason is to do something out of the ordinary to prompt the children to ask questions as writes Dibré Shalom VeEmet (Heleq 2, Pesahim 115b, ibid.).

2) It acts as a remembrance for the ‘Anané HaKabod (Clouds of Glory) that HaShem used to guide and protect Bené Yisrael in the wilderness for forty years. The circling of the qe’ara is alluded to in the pasuq (Shemot 13:18) “Vayaseb Eloh-im et ha’am derekh hamidbar yam suf…” – “And God circled the people toward the way of the wilderness to the Sea of Reeds….”

3) Ribi Hayim Palaji (Hayim LeRosh, Magid Siman 10) writes that the qe’ara alludes to the 10 misvot that correspond to the 10 sefirot (Celestial/Qabalistic Spheres) whose merit protects the Jewish people. With the “Bibhilu” ritual, the berakha represented in these spheres will fall upon the person beneath the plate. This explains why the plate is lowered and softly bumped on the person’s head; as a sign that the berakha should come down onto the person.

4) There is an allusion to this minhag in the pasuq (Tehilim 26:6) “…va-asobeba et mizbahakha Ado-nai” – “…and I circle around Your altar, HaShem”). The word mizbahakha can be an acronym for: Masa, Maror, Zero’a, Besa, Haroset, Hazeret, Karpas, all of which are the items present on the qe’ara with which is circled.[23] Pesah is also called Hag HaAbib (the Spring Holiday) so they would use a flowerpot, specifically a gladiola, to symbolize the beginning of Spring. This is known to be the tradition of Marrakech as heard in the name of Ribi Reuben Abitbol.[24] Generally speaking much is done to increase the happiness of the night and create a pleasant ambiance. Therefore, everyone in the family is acknowledged even in their absence. See Osrot HaMaghreb (Pesah).[25] A similar minhag is observed regarding Kaparot on Yom Kipur there the chicken/money is waved over each person’s head four times. See Qobes Minhagim (Pesah).[26] As commonly witnessed in Meknes, this tradition further express the implications of the sederplate (qe’ara) and all that it contains, see Meknes’ Iri (Pesah).[27] Acting and involving those present further publicizes the obligations of the night. See Qobes Minhagim (Pesah).[28] This is the common Moroccan minhag. Ribi Ya’aqob Benaim s”t (Maghen Abot, O”H p.427 §64) confirms that this was the minhag of Tetouan and its surroundings.[29] The wine is considered to have a ruah ra’a (a bad spirit) as it was used to commemorate the plagues, which is weakened by water. It is for this reason that the posqim advise spilling the wine into a broken container and then disposing of the contents outside in a place where people do not normally walk.[30] Even though Shulhan ‘Arukh does not mention them, Ribi Yosef Messas lists in one of his letters (Osar HaMikhtabim Heleq 2 §1128) the ingredients with which Moroccans customarily made haroset. Dates are added as a reminder of the pasuq (Shir HaShirim 7:8) “Your stance is like a date palm….” The Maté Moshé corroborates this and adds that raisins and wine are also used as a reminder of the grape vine to which Jews are compared. Rema lists the recipe for haroset (O”H Siman 473:5) where the Mishna Berura further explains that each of the ingredients can be compared to Bené Yisrael and are all derived from pesuqim in Shir HaShirim.[31] See Ribi Barukh Toledano (QS”A Siman 311:18) and Pé Yesharim (p.27). Lettuce in Aramaic is hazeret, also called hasa, which alludes to HaShem’s mercy falling (“has”) on us. Some have the minhag to use endives as maror.[32]Kos Eliyahu[33] See Pé Yesharim (ibid.) by Ribi Habib Toledano and the QS”A (Siman 311:27) by Ribi Refael Barukh Toledano who write extensively about the great prohibition of eating insects. The QS”A writes that one must check each leaf individually at least three times. He explains further that it is better for one who does not have properly checked lettuce to not eat it at all, or just eat the stalk. The Ko LeHai (p.121) writes that one must check the stalks many times with light from an electrical source. See Leb Mebin (Y”D Siman 99), Yismah LeBab (Y”D Siman 14), and Peri Toar (Siman 15) who also discuss the gravity of eating insects.[34] Since the paragraphs of Pesah, masa, and maror make up the main portion of the hagada until “Amar Raban Gamliel,” anybody that does not say these three things on Pesah and understand them is not fulfilling their obligation. Therefore, much emphasis is put on saying them.[35] This is to exemplify the love that the Jewish people have for the misvot, specifically the misva of masa, which is called by the Zohar “Nehema Dimhemnuta” – “Lehem HaEmuna” (The Bread of Faith). Similarly, the same act of kissing is done when performing many misvot such as donning tefilin and shaking the lulab.[36] From here on out, the reader of the hagada recounts in depth the misvot of the night, and gratitude is given to HaShem for all that He did for the Jewish people. See Qobes Minhagim (Pesah) and Osrot HaMaghreb (Pesah).[37] In accordance with the ruling of Ribi Shalom Messas (Mizrah Shemesh 98:1 & Shemesh Umaghen Heleq 2, Siman 73 and Heleq 3, Siman 45) which contrasts the ruling of Ribi Maimon Berdugo in his Leb Mebin, who writes that his father, HaMal-akh Refael Berdugo, measured kezetim in weight.[38] The Moroccan minhag is to follow this opinion, specifically as confirmed by Ribi ‘Amram Assayag s”t and Ribi Mordekhai Lebhar s”t. Sefaradi posqim contend that a kezayit is 28 grams; included among them Ribi Shalom Messas in the approbation to Miqra-é Qodesh by Ribi Moshé Harari, and Debar Emet (Siman 1).[39] See Pé Yesharim (p.27) by Ribi Habib Toledano.[40] See Kos Eliyahu (p.21) who says that the majority of Moroccan posqim rule that the size of an egg has not diminished over time, which puts the required amount to drink at 80ml. See Rashbash (Siman 44), Mayim Hayim (Heleq 2, Siman 14), Debar Emet (ibid.), VaYomer Yishaq (Siman 7), Yismah LeBab (Siman 8), and the hagadaKo LeHai (p.79).[41] This is the minhag of Marrakech. See Noheg BeHokhma (p.164), Osrot HaMaghreb, and Ta’amé HaMinhagim (p.283).[42] The doors are left open to demonstrate that the misvot guard and protect a person, that one has no one to rely on for protection except for our Father in Heaven, and that there is no fear of the gentiles. At what better time to do this than right before Halel when all the misvot of the night have been fulfilled; a night that is nicknamed “Lel HaShemurim” (The Night of Guarding). See QS”A (Siman 428:3), Osrot HaMaghreb (Pesah), Mo’adé HaShem (p.302), and Rema (Siman 480:1). To read more about this see mahzorMo’adé HaShem.[43] This is done because the spiritual importance of “Nishmat kol hai” is very great, especially on Pesah night when the concept of protection is greater than any other night of the year.[44] “Shir HaShirim” illustrates the unconditional and everlasting love between HaShem and the Jews and is said at this point to highlight this central theme of the night.[45]Had Gadya is a deeply spiritual poem that serves as a metaphor for the entire history of the Jewish people’s persecution and subsequent salvation through God’s hand. Even though it might sound like a “simple” poem, Ribi Ya’aqob Abihsera (Abir Ya’aqob) at the end of his sefer Bigdé HaSerad, writes two long explanations for each line of the poem, one based on the literal meaning and one based on the deep Qabalistic secrets contained within it.

Pesach Lists for Sepharadim

Sign up for the Daily Moroccan Halachot Email