Halachot in the tradition of our Chachamim from Morocco

Dozens of Audio & Video Shiurim by Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar

Hilula of Moroccan Tzadikim

Sefarim based on our Morrocan Minhagim

Monthly Sponsor: Available

Weekly Sponsor: Available

Sponsor of the Day: Available

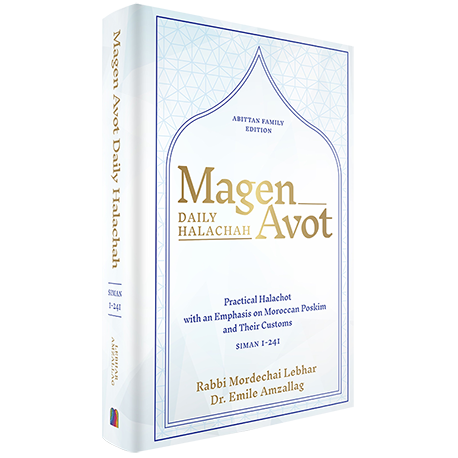

Magen Avot - Daily Halacha

Click here to purchase

Daily Moroccan Halachot

Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar, author Magen Avot

Redacted by Dr. Emile Amzallag

DAILY HALACHOT PODCAST  ON APPLE

ON APPLE  ON SPOTIFY

ON SPOTIFY

Daily Halachot Topics

The section of the prayer preceding the blessings of Keriat Shema is known as Pesuke Dezimra, and is a collection of chapters of Tehillim and other sections from the Torah. Pesuke Dezimra is book-ended by two blessings; Baruch She’amar at the beginning and Yishtbah at the end. In the Ashkenazic community, the verses of Hodu are included in the Pesuke Dezimra while among Sepharadim, Hodu comes before Baruch She’amar. The Arizal explains the Sephardic custom by saying that whereas Pesuke Dezimra contains discrete chapters of Tehillim, Hodu and the verses following it are a collection of verses from different parts of the Tanach, and thus are not to be included. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 5, § 1) writes that if a Sephardic person is called up to be Shaliah Tzibbur at an Ashkenazic synagogue, he may recite Hodu after Baruch She’amar because even this custom has Kabbalistic sources. Furthermore, if one forgot to recite Hodu and started Baruch She’amar, one may recite Hodu within Pesuke Dezimra. At the end of Hodu, the verse “Hodu L’Hashem Ki Tov Ki Le’olam Hasdo” is recited. Even though the Ben Ish Hai (Od Yosef Hai, Parashat Miketz, § 13) says that this verse should not be repeated, the Siddurim Tefilat HaHodesh and Bet Oved both have this verse written twice, and this is the Moroccan custom. After Hodu and before Baruch She’amar, Mizmor 67 (“Lamnatze’ah Binginot Mizmor Shir”) is recited and should preferably be read in the shape of a Menorah. If one does not have access to this format, one should imagine the shape of a Menorah, and it is brought down that one who recites it in this manner will be protected throughout that day. On Shabbat and Yom Tov, this chapter is replaced by Mizmor 19 (“Lamnatze’ah Mizmor Ledavid”). The Kaf HaHaim (K.H., O.H. 50) writes that the custom of the Bet El community to recite Mizmor 19 even on Hol HaMo’ed, and the Ben Ish Hai (Parashat Vayigash, § 4) says that this is logical since Hol Hamo’ed has attributes of Yom Tov. This is also the Moroccan custom. Summary: Hodu is recited before Baruch She’amar, but may recited after if one forgot to recite it or if one is serving as Shaliah Tzibur with Ashkenazim. “Hodu L’Hashem Ki Tov” is said twice at the end of Hodu. On a weekday Mizmor 67 is said before Baruch She’amar whereas on Shabbat, Yom Tov and Hol Hamo’ed, Mizmor 19 is recited in its place. At the beginning of the Shaharit prayer, there is a section referred to as Korbanot which is recited. This is a generic term for a collection of Torah, Mishna and Gemara passages that discuss different aspects of sacrificial offerings and serve as an introduction to the morning prayer. The Torah portion which is recited is that which deals with the Tamid offering (“Tzav Et B’nei Israel…”), which was offered every morning (and every afternoon). Following this is a section from the Gemara (Keritut 6a) which discusses the Ketoret, or incense offering. Finally, the fifth chapter of the Mishna in Zevahim, referred to as Ezehu Mekoman (since these are the first words of the chapter) is recited, and this discusses different aspects of the offerings. It should also be noted that the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 50:1) says that the reason that the Tamid, Ezehu Mekoman and, later on, the Baraita of Rabbi Yishmael are recited is so that every person is guaranteed the opportunity to learn at least some Torah, Mishna and Gemara every day. Interestingly, the section of of Ezehu Mekoman was chosen for the Mishna portion because this chapter contains no rabbinic disputes and is considered to contain clear Halachot directly from Mount Sinai. If one has limited time, it is preferable to recite the Tamid portion over Ezehu Mekoman or the Baraita. Even though there is no opportunity to offer sacrifices nowadays, the Midrash (Midrash Rabba, Bamidbar 18) teaches that the recitation of passages which deal with the offerings is akin to actually participating in the sacrificial rituals. Indeed, the Magen Avraham (M.A., O.H. 48:1) says that since the sacrifices were performed standing up, the recitation of these passages should also be done while standing up. Nevertheless, the Mishna Berura (M.B., O.H. 48:1), cites the Sha’are Teshuva, who in turn quotes different Aharonim like the HIDA (Mahzik Beracha), who say that Korbanot are recited while sitting, and this is the common custom. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 48:1) states that that on Shabbat, the verses dealing with the Shabbat Musaf offering (“Uvyom HaShabbat..”) are added to the Tamid portion. On the other hand, the Shulhan Aruch continues, on Rosh Hodesh and Yom Tov, the verses corresponding to those days’ offerings are not added to the recitation of the Tamid since they will be mentioned in the Musaf prayer. The Rama (ibid.) adds that on Rosh Hodesh, the verses for that day’s offerings (“Uvrashe Hodshechem”) are also said. The Kaf HaHaim (K.H., O.H. 48:5) says in the name of the Arizal, that even the verses of Shabbat are not recited, and th HIDA testifies that this was the custom in Israel also. Nonetheless, Rabbi Moshe Malka (Mikve HaMayim, vol. VI, § 10:2), and Rabbi David Ovadia (Nahagu Ha’am) who cites Rabbi Ya’akov ibn Tzur, both write that the custom in Morocco was to follow the opinion of the Shulhan Aruch and only add on the verses for Shabbat. Summary: There is great significance to reciting the Korbanot section at the beginning of Shaharit. The Moroccan custom is that on Shabbat the verses pertaining to the Shabbat Musaf offering are added to the Tamid, and all the Korbanot are recited while sitting. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 47:10) writes that a settled sleep on one’s bed during the day is considered an interruption with regards to Birkot Hatorah and that one would have to repeat them after sleeping. Some, however, maintain that it is not an interruption and the Shulhan Aruch mentions that this is the common custom. The Ra’ah (Berachot 11b) explains that one reason that it is not considered an interruption is because for the general population the daytime is not a time for sleeping, even if for an individual it may be so. Therefore because of this and because of the general principle of Safek Berachot Lehakel, one who wakes up from a daytime nap would not repeat Birkot Hatorah. One practical implication of this Halacha involves taking a short nap at night, such as if one naps after the Shabbat night meal and then wakes up to learn. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 4, § 6) says that if one napped in one’s bed for at least thirty minutes, one would be required to repeat Birkot Hatorah upon waking up. Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer, vol. VIII, § 5:5) says that if one napped for just a few minutes, and even if one remained in one’s clothing, one would need to repeat the blessings. Furthermore, if one’s nap began in the daytime and extended even a few minutes into the night, one would be required to repeat Birkot Hatorah. It has been said of Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach that he would nap after the Shabbat night meal with his clothes and for this reason he would not repeat Birkot Hatorah. When it comes to staying up all night, the Magen Avraham posits that the Shulhan Aruch (ibid.) seems to imply that one would not recite Birkot Hatorah and would rely on the Birkot Hatorah that were recited the previous day. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (ibid., vol. III, ch. 18) says that there are those who write that according to Kabbalah one would be required to recite Birkot Hatorah at dawn. Nevertheless, the Moroccan custom is based on the Magen Avraham‘s inference on the Shulhan Aruch which implies that when one stays up all night, such as on Shavuot, one should rely on the blessings of someone who and will have one in mind. Even though the other Birkot Hashahar can be recited even if one stayed up all night, the custom is that since one will hear Birkot Hatorah from someone who slept, then one will have that person recite all the blessings on one’s behalf. It should be noted that if one stays up all night, one does not recite “Al Netilat Yadayim”. Summary: One does not repeat Birkot Hatorah after a daytime nap. One should repeat Birkot Hatorah if one naps at night and wakes up to learn. If one stays up all night, one should have someone who slept recite all the Birkot Hashahar and Birkot Hatorah on one’s behalf. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 37:3) states that a father must purchase Tefilin for a minor who can control himself from falling asleep, passing gas or going into the bathroom while wearing them, in order to train him in this Mitzvah. Based on this ruling, it was common in Morocco for boys to celebrate their Bar Mitzvah by wearing Tefilin and being called up to the Torah before the age of thirteen. This is echoed in Siddur Bet Oved (Hilchot Tefilin, § 4). Rabbi Yosef Messas (Otzar Hamichtavim, vol. III, § 843) writes that a boy could begin wearing Tefilin as early as age seven, although more commonly it was done at eleven years old or so. (c.f Rabbi Yosef Messas Mayim Haim, vol. II, § 1). Interestingly, in Morocco, one’s Bar Mitzvah was called simply “Tefilin”. It goes without saying that even though the rite of passage was observed at an earlier age, one only acquires the Halachic status of an adult as of age thirteen. The Rama (ibid) mentions that one should wait until one is specifically thirteen years old before starting to wear Tefilin, and Rabbi Yitzhak Ben Oualid (Vayomer Yitzhak, Orah Haim, Hilchot Sefer Torah, § 15) writes that one should wait till this age before being called up to the Torah. Nonetheless, the custom was to allow it earlier as mentioned above. Regarding “Sheheheyanu”, the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 22:1) writes that one recites this blessing when donning a new Talit for the first time. Rabbi Yitzhak Ben Oualid (ibid., Hilchot Berachot, § 23) and Rabbi Shlomo Dayan (Ateret Shlomo, § 3) says that this blessing would be recited when placing Tefilin for the first time and this appears the custom. Rabbi Chaim Pinhas Scheinberg is of the opinion that “Sheheheyanu” is not recited since an animal had to die for the Tefilin to be made, which takes away from the requisite joy to recite this blessing. Rabbi Shalom Messas (approbation to Ateret Shlomo), writes that in Meknes, Morocco, the custom was to have the child don the Talit followed by the Tefilin and then to recite “Sheheheyanu” on the Talit and have in mind to exempt the Tefilin. Summary: A child may begin wearing Tefilin with a blessing before the age of thirteen, so long as he knows how to control his bodily functions. A Bar Mitzvah boy recites “Sheheheyanu” over a new Talit and has in mind that the Tefilin is included in this blessing The typeface used by the Sephardic community, including in Morocco, for writing Torah scrolls, Tefilin and Mezuzot is known as Valish, which comes from the Old German word for “foreign”. Rabbi Yaakov Emden, who hailed from Denmark, promoted this type of script. On the other hand, the Ashkenazic community uses a typeface that was promoted by the Bet Yosef, based on the book Baruch She’amar. One of the features of the Ashkenazic script is that it is more ornate than the more basic Valish font, and the details on each letter have Kabbalistic significance. For example, the letter Yud, has a small projection which extends downwards from the top left of the letter, known as Kotzo Shel Yud (lit. “the Yud’s thorn”). Another example of a difference is the letter Het, which in Morocco was written like Rashi (Shabbat 104) describes as a Resh connected to a vertical line. On the other hand in the Ashkenazic script, the Het is written with two Zayins connected on the top by a pointed “roof”. When asked, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef answered me that the Het should be written like the latter style. Most scribes nowadays, Sephardic and Ashkenazic alike, write Torah scrolls, etc. with the more detailed script and indeed Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II) questions why any scribe would not try and be more stringent and incorporate these details. Although traditionally the Sephardic community used Valish, incorporating a more ornamental motif does not abandon the Valish tradition font but rather adorns and augments it. That being said, according to Halacha, as long as each letter is recognizable and legible, the scroll is valid. For this reason, Rabbi Haim Volozhin and others write that a Sephardic person fulfils one’s obligation when reading from a Torah written in the Ashkenazic font, and vice versa. Summary: The typeface historically used by the Sephardic community for Torah scrolls, Tefilin and Mezuzot is Valish. There is no issue of using the typeface used by the Ashkenazic community.

The previous Halacha mentioned that although the custom in Morocco was not to wear Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam because of the appearance of haughtiness, there are opinions that this is no longer concern. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 34:2) records three opinions of how the Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam should be placed vis-a-vis Tefilin of Rashi. The first approach is that both types of Tefilin are donned simultaneously, but as mentioned in a previous Halacha, there is an opinion that only the area of the biceps closer to the elbow is valid, and thus it may be difficult to place both Tefiln Shel Yad. The next option is that one type of Tefilin is placed with a blessing, and then immediately removed so that second type can be placed, and the Shulhan Aruch does not mention which comes first. The third opinion and that which is most commonly practiced, is that Tefilin of Rashi are placed first with a blessing and are left on for the duration of the prayer. After the Amida, they are removed and Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam are placed without a blessing. Rabbi Kalifa ben Malka (Kaf Naki, Hilchot Tefilin) of Agadir, Morocco cites Rabbi Yitzhak Nahon of Tetouan, who says that it is preferable to place one type of Tefilin after the other, and there is no concern of appearing overly-religious, since they are placed in sequence and not simultaneously. On the other hand, according to the Mekubalim, each type of Tefilin has its unique significance and intention, and thus should specifically be donned at the same time. Indeed, the Ben Ish Hai, following the opinion of the Vilna Gaon, says that the entire length of the biceps muscle is valid. Nevertheless, this goes against the opinion of the Shulhan Aruch which only permits the half closer to the elbow, and practically speaking, fitting both types of Tefilin is unrealistic in most instances . Accordingly, Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II) and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer, vol. I, § 4) both say that if there is not enough room on the biceps, the Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam should be placed after the Tefilin of Rashi are removed. Interestingly, Rabbi Kalifa ben Malka writes (and even summarized his words in a poem) about three other types of Tefilin in addition to Rashi and Rabbenu Tam, namely the Shimusha Raba, the Arizal and the Raavad. Since there are multiple types he offers a novel way to fulfil all opinions: Rashi Tefilin should be donned daily; the Tefilin of the Arizal should be placed on public fasts; the Shimusha Raba should be worn on Rosh Hodesh; Raavad during Aseret Yeme Teshuva; and the Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam should be placed on the day following Yom Kippur. He mentions that after Yom Kippur one is purified from any sins and one is considered to be a Hasid, a pious person. Since one is given this status of being pious, one can take that opportunity and place the Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam without the concern of appearing overly-religious or haughty. Although no one follows this stringency, it demonstrates the meticulousness with which our Hachamim were about keeping the Mitzvot. Summary: If one has the practice of wearing Rabben Tam Tefilin, they should be donned after the Amida, once the Rashi Tefilin are removed. No blessing is recited when the Rabbenu Tam Tefilin are placed. The Gemara (Menahot 34b) discusses that the box of the Tefilin Shel Rosh and Shel Yad contain four compartments, each with a different portion from the Torah.. These four portions are “Kadesh Li”, “Vehaya Ki Yeviacha”, “Shema Israel” and “Vahaya Im Shamo’a”. Rashi interprets the Gemara as saying that the order of these portions is as they appear in the Torah, that is, in the aforementioned order. Rabbenu Tam, on the other hand, says that “Kadesh Li” and “Shema Israel” should be in the outer compartments and both portions that begin with “Vehaya” should be next to each other in the inner compartments. It is important to note that although this disagreement is commonly attributed to Rashi and Rabbenu Tam, it existed much earlier. In fact the Zohar cites an opinion in the Talmud Yerushalmi which is in accordance with the opinion commonly attributed to Rabbenu Tam. The Rambam (Shu”t HaRambam, § 19) writes that the Rif was influenced by the writings of Rabbi Moshe bar Maimon (not the Rambam), who wrote like Rabbenu Tam’s opinion. Afterwards, a certain Rabbi Deri travelled from Morocco to Israel, and taught that the Tefilin should be like the opinion attributed to Rashi, and thus the Rambam ruled as such. Due to this long standing disagreement, the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 34:2-3) says that both types of Tefilin should be donned, but only by those who are Gd-fearing and that are known to be pious. If one is not of such a spiritual caliber, donning both types of Tefilin may seem haughty, as though one is trying to appear overly religious. In Morocco, there was a general awareness about appearing haughty and thus Rabbenu Tam Tefilin were not commonly worn. Some rabbis would wear them, but would do so privately. Rabbi Shalom Messas (Tevuot Shamesh) writes that even though it was not common even among rabbis, he wished to be stringent and adopt the custom of wearing Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam. At the age of thirty, he became sick with typhus and attributed it as being a heavenly sign that he was acting arrogantly by adopting this practice, and stopped doing it altogether. That said, the HIDA (Mahzik Beracha), is of the opinion that nowadays wearing Rabbenu Tam Tefilin in addition to Rashi Tefilin is not considered haughty. Indeed, it is not uncommon for people to don both types of Tefilin, and Rabbi Ovadia Yosef was a proponent of this practice. As such, Rabbi Elyashiv and others are known to have said that since it is more common, one need not be concerned about appearing overly religious or haughty and one can take on this practice. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II) writes that an unmarried man should not don Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam since one may have impure thoughts. This is based on the Shulhan Aruch (O.H 38:4), which says that one’s thoughts must not have lustful thoughts while wearing Tefilin. A married man, on the other hand, is considered to have attained a level at which one’s thoughts are more controlled and thus is fit to wear both types of Tefilin. Nevertheless, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Halichot Olam) says that a single man may wear Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam as long as he is sure that he can control his thoughts. Summary: The Moroccan custom was for lay people to not wear Tefilin of Rabbenu Tam. If one wishes to take on this practice, one need not be concerned about appearing haughty. The box of the Tefilin contains four parchments, each with a different portion from the Torah. There is a disagreement between the Rambam and the Rosh as to which portions need to be open and which need to be closed. In this context, open means that the beginning of the Torah portion is written at the right margin of the column, while closed means that the portion begins in the middle of the column. The Rambam asserts that the first three portions in the Tefilin need to be open and the last should be closed, while the Rosh says that all portions should be open. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 32:36) rules in accordance with the Rambam and says that if the fourth portion is not closed, the Tefilin are invalid. The Taz (O.H. 32:26) seeks a compromise between the Rambam’s and the Rosh’s opinions by saying that the fourth Torah portion should begin in between the right margin and the center of the column. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 3, § 7) writes that the Taz’s approach is rejected by the Shulhan Aruch and that the Sephardic community does not rely on the Taz. On the other hand, the Ashkenazic community does follow the Taz’s view and thus if a Sephardic person borrows Ashkenazic Tefilin, a blessing should not be recited over them. The Chabad community follows the opinion of Rabbi Shneur Zalman, who sided with the Rambam, and thus a Sephardic person could use Chabad Tefilin and recite a blessing. An Ashkenazic person who wishes to use Sephardic Tefilin may do so and recite a blessing since the Vilna Gaon also followed the Rambam’s view. Indeed, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach was known to wear Tefilin according to the custom of the Vilna Gaon. Summary: A Sephardic person may wear Ashkenazic Tefilin but should not recite a blessing. One may also wear Chabad Tefilin and one would recite a blessing. The Mitzvah of Tzitzit is only applicable in the daytime since the verse states “Uritem Oto” (lit. “and you shall see it [the Tzitzit]”) and seeing is considered only possible during the day. On the other hand the Gemara (Menahot 36b) says that the Mitzvah of Tefilin is in the day and at night as well. The reason that Tefilin are not worn at night, however, is because one may fall asleep and pass gas while wearing them and this would be considered disparaging to the Tefilin. As well, by falling asleep one loses the proper concentration that is necessary while donning Tefilin. Thus, even though on a biblical level one may don Tefilin at night, the Rabbis forbade it. It should be noted that this is not considered a full fledged Rabbinic decree (Gzera) such as not blowing the Shofar on Shabbat (lest one carry the Shofar in the public domain) or riding an animal on Shabbat (lest one tear a tree branch to use in directing the animal), but rather a lesser enactment. One practical application of this Halacha is when Tefilin are worn during Minha of a public fast. Very often, the Minha prayer can extend past sunset while the congregants are still wearing Tefilin. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 30:2) writes that it is forbidden to don Tefilin at night, but that if one already had them on and the sun set, one may continue wearing them. Although this is the Halacha, the Shulhan Aruch states that one does not go out of one’s way to teach that Tefilin hypothetically could be worn at night. Practically speaking, however, if one is in the aforementioned scenario, one may wear the Tefilin a little but after sunset until the Minha prayer finishes. The Shulhan Aruch continues and says that if the sun has set and there is no where to safely keep one’s Tefilin, one may wear them until one gets to a place where they may be kept. Nevertheless, the Mishna Berura (O.H. 30:15) and the Ben Ish Hai (Parashat Vayakhel), who both cite the Arizal, say that the Tefilin should not be worn at all after sunset. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (Igrot Moshe, vol. I, Orah Haim, § 10) responds to a question from someone who worked for the Russian government from very early in the morning till the night and did not have the opportunity to put on Tefilin. Normally, the time of Tefilin is from the time that there is sufficient light for one to recognize one’s fellow (O.H. ibid:1), roughly six minutes after dawn, till sunset. Regarding one who needs to don Tefilin before dawn, the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. ibid:3) says that one may wear them and when the Halachic time comes, one should shake them and recite the blessing while wearing them. However, the above case involved one who would wear Tefilin and remove them before dawn. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein responds that, as mentioned initially, the prohibition to wear Tefilin is not a Rabbinic decree but rather a prohibition based on a concern of falling asleep. Therefore, he permits wearing and removing the Tefilin before dawn, and to even recite a blessing, especially in light of the fact that in this case, such a person would never have an opportunity to wear Tefilin and may forget about this Mitzvah. If one is learned and is faced with this situation, one should not recite a blessing. Summary: Tefilin are not worn at night. If one is wearing Tefilin close to sunset, one may keep them on a few minutes after sunset if necessary.When is Hodu recited?

What are “Korbanot”?

Birkot Hatorah after a nap?

Celebrating One’s “Tefilin”

Can a child wear Tefilin?

Sephardic Font

What Typefce is used in Tefilin?

How are Rabbenu Tam Tefilin Donned?

Tefilin: What is Rabbenu Tam?

Rashi והיה אם שמוע שמע והיה כי יביאך קדש Rabbenu Tam שמע והיה אם שמוע והיה כי יביאך קדש Ashkenazi Tefilin

Can Ashkenazi Tefilin Be Worn By Sephardim?

Tefilin at Night?

How are Tefilin Removed?

The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 28:2) says that when removing the Tefilin, the Tefilin Shel Rosh are removed first. This is learned from the verse “Totafot Ben Enecha”, that when one wears the Tefilin between one’s eyes (that is, Shel Rosh), one should on have both Tefilin (Totafot is plural). This is not so regarding Tefilin Shel Yad and so it follows that The Tefilin Shel Yad are removed afterwards. Furthermore, the Tefilin Shel Rosh and Shel Yad should be removed in the manner that they are placed, that is, standing and sitting, respectively.Rabbi Israel Elnekave (Menorat Hama’or, vol. I, pg. 70) writes that there is a custom to wrap the Tefilin Shel Rosh, and according to the Ritva (Shabbat 49a) the Tefilin Shel Yad as well, like the wings of a dove to commemorate the miracle of Elisha Ba’al Haknafayim. The Gemara (Shabbat 49a) which relates the story of a certain Elisha who was wearing Tefilin during a Roman decree which forbade donning Tefilin under penalty of death. When a Roman official approached him he quickly removed his Tefilin Shel Rosh and the Roman asked him what was in his hands. Elisha responded that he had dove wings in his hand and miraculously real dove wings appeared, and henceforth he was referred to as Elish Ba’al Haknafayim. The Gemara explains that this even involved a dove because a dove uses its wings to protect itself from predators. Just as the dove’s wings protects the dove so too the Mitzvot, such as tefilin, protect the Jewish people. Indeed there is a custom that can still be observed among older Moroccans to fold the straps of the Tefilin Shel Rosh like dove wings.The Magen Avraham (O.H. 28:4) writes that there is an opinion that the straps should not be wrapped directly onto the box of the Tefilin since the latter have a higher level of holiness. As such, there is an added benefit for wrapping the straps like dove wings since the will not come into contact with the box. Nowadays most Tefilin are placed in a protective case to prevent the straps from touching the box, but the it is still proper to wrap them like dove wings.The Shulhan Aruch (ibid:3) also says that it is the custom of Torah scholars to kiss the Tefilin when donning them and when removing them. The Ben Ish Hai adds that once they are wrapped and ready to be put away, they should also be kissed to show love towards the Mitzvot.Summary: The Tefilin Shel Rosh are removed before the Tefilin Shel Yad and this is done standing up. The Tefilin Should be kissed upon their removal.

Sign up for the Daily Moroccan Halachot Email