Halachot in the tradition of our Chachamim from Morocco

Dozens of Audio & Video Shiurim by Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar

Hilula of Moroccan Tzadikim

Sefarim based on our Morrocan Minhagim

Monthly Sponsor: Available

Weekly Sponsor: Available

Sponsor of the Day: Available

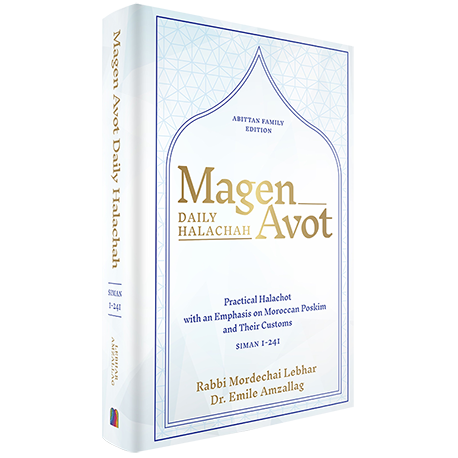

Magen Avot - Daily Halacha

Click here to purchase

Daily Moroccan Halachot

Rabbi Mordechai Lebhar, author Magen Avot

Redacted by Dr. Emile Amzallag

DAILY HALACHOT PODCAST  ON APPLE

ON APPLE  ON SPOTIFY

ON SPOTIFY

Daily Halachot Topics

The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 55:20) says that if one is in the vicinity of, but not a part of a Minyan, one may answer Kaddish or Kedusha that is being recited in that Minyan. The Shulhan Aruch seems to imply that one is not obligated to answer, but may do so if one wishes [as to why one would not be able to answer, see below]. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, ch. 45, § 12) says that if one is learning Torah, for example,in an adjoining room or in the sanctuary where the Minyan is praying, one does not have to interrupt one’s learning to answer “Amen”. On the other hand, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (Halichot Shlomo, ch. 9, § 6) says that if one is in another room, one need not interrupt one’s learning to respond to parts of the prayer. If one is in the same room as the Minyan, however, he says that one would not need to respond to Kaddish, but that it would be unseemly to ignore Kedusha, Modim and Berechu and that, therefore, one would need to answer. Tangentially related to this is the concept of Amen Yetoma, or an orphaned Amen. Amen Yetoma refers to an “Amen” that one recited but did not hear the blessing or part of the prayer, and thus the Amen is “orphaned” from that blessing, as it were. The Rama (O.H. 56:1) states that if one walks into a Minyan and hears the congregants answering Kaddish, one may also respond, even though one did not hear the Kaddish being recited. Since the person knows that it is Kaddish that is being responded to, the Amen is not orphaned. This is similar to the Gemara’s (Sukkah 51b) description of a very large synagogue in Alexandria, Egypt in which flags would be waved in order for the distant congregants to be able to know when to answer the prayer. In a similar vein, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yehave Da’at, vol. II, § 68) says that if there is a Minyan and one is listening to the Minyan live on the radio, one is able “Amen” to the different parts of the prayer, and it would not be considered an Amen Yetoma. This would seem to apply if one is watching live on television or if it is being broadcast live on the internet. It should be noted that one’s obligation for a particular Mitzvah cannot be fulfilled in this method, such as if one were to hear the blessings and recital of Megilat Esther or Havdala. Summary: If one is not participating in a Minyan but is in the same area, one is not obligated to respond to Kaddish, but may do so if one wishes. One should, however, respond to Kedusha, Modim and Barechu. One may answer “Amen” to a prayer or blessing that is recited over a live broadcast. The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 55:13-20), explains the parameters of where members of a Minyan must be located in order to be counted as part of that group. One case (ibid:16), which is based on a discussion in the Gemara (Eruvin 92), is when there is small room which opens up to a large room. In such a case, if one person (or the minority), for example is in the small room and nine (or the majority) in the large room, then the small room is considered an annex to the larger room and therefore, the person in the small room becomes incorporated into the group in the larger room. If, however, there are nine people in the small room and only one in the large room, then the minority does not become incorporated into the majority since the large room cannot be considered an annex to the smaller room. Another case is when there are nine people in the sanctuary and the Shaliah Tzibur is on a raised and enclosed Teva. The Shulhan Aruch, nased on the Rashba (Teshuvot HaRashba 96), rules that despite the Teva appearing to be a separate entity, it is part of the remainder of the sanctuary and the Shaliah Tzibur counts towards the Minyan. These examples are relevant since many of the Tevot used in Morocco were enclosed with walls and were raised slightly. Furthermore, it is common nowadays to have a synagogues with a Mehitza on the same floor which sections off an area of the sanctuary. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. I, § 15) writes that these areas are part of the larger sanctuary and therefore so are those praying within them. Additionally, Rabbi Yitzhak Assebag (Ohel Yitzhak) [also known as the Pahad Yitzhak and was the mentor of Rabbi Shalom Messas] writes that an elevated Ezrat Nashim (women’s section) which is separated by a Mehitza is considered as part of the sanctuary, and so if a man is located there he could count as part of the general Minyan. It does not appear that this ruling also applies to a balcony-type Ezrat Nashim, but it is possible that even in that case, if the person in the balcony can make eye contact with those below, he might be counted towards the Minyan. The aforementioned ruling of the Shulhan Aruch refers to two distinct rooms which open up to each other. However, in a sanctuary where there is an area which is partitioned off, or which has a smaller connected room off to the side, it is all considered one continuous area. As such, even if the minority of the group is in the larger section, it can combine with those in the smaller area to form a Minyan. Summary: One can be counted towards a Minyan if one is located in a partitioned area of a sanctuary, in a side room with an open connection, in a slightly elevated women’s section or in the Teva. Although the practice is to face towards the Bet HaMikdash-in most cases, east-when praying, there does not appear to be a hard and fast rule with regards to the recital of Kaddish. Rabbi David Ovadia (Nahagu Ha’am, Hilchot Kaddish) writes that in Morocco, the custom was that Kaddish did not necessarily have to be recited facing east. This is relevant when Kaddish is recited around a table during a meal and the like, and the custom is to not be particular about finding which way is east. Evidently, if one is in the sanctuary of a synagogue, it is not proper to have one’s back towards the Hechal, but otherwise there is more leeway. Rabbi Yosef Messas (Otzar Hamichtavim, vol. III, § 1843) writes that if a child is donning Tefillin, then he can certainly be counted towards a Minyan, and said that he witnessed this practice during his time in Algeria. Similarly, Rabbi Baruch Toledano (Kitzur Shulhan Aruch, § 12) says that when necessary a child may be counted towards a Minyan. Nevertheless, Rabbi Shalom Messas (Shemesh Umagen, vol. IV, § 17) rejects this position and says he never heard of such a concept. In any case, it should be noted that a child should never be counted towards a Minyan a priori, or on a consistent basis, but rather in a time of necessity. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 5, §4) says that if one finds oneself in a Minyan that includes a minor, one may answer “Amen” to the blessings of the Amida or to Kaddish and the like, since there are opinions which support including a minor. On the other hand, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer, vol. IX, § 120:33), consistent with his position of not answering “Amen” to things that are counter to his Halachic methodology, says that categorically that one should not respond “Amen” in such a Minyan. Summary: There were places that were lenient that a minor who is at least six years old and knows that it is Hashem Who is being prayed to, may be counted towards a Minyan. An adult who is part of such a Minyan may answer “Amen” and any other responses that are recited among a Minyan.

Often times, words are repeated in certain parts of the prayer so that the words fit well with the particular tune being chanted. Rabbi Yehuda Modena (Zikne Yehuda, § 131), Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (Igrot Moshe, vol. II, Orah Haim, § 22) and the Aruch HaShulhan (§ 58) all reference the Mishna (Berachot 5:3) when discussing this situation. The Mishna says that if during the prayer one says “Modim, Modim” rather than just “Modim”, one should be silenced since it appears that one is praying to two deities. That being said, if the words being repeated do not give the appearance of praying to two deities, then it would seem that it would be permissible. There is no clear proof among the Poskim as to whether repeating words is forbidden or permitted, but many say that it should be avoided if possible. Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 7, § 39) says that it is preferable to use tunes which do not require repeating words, but that if there are tunes which have been chanted for generations which involve repeating words, then there is room to be lenient. Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (ibid.) says that if by repeating words the meaning of what is being chanted changes then it should be avoided. For the most part, repeating words does not alter the meaning of the prayer and therefore, if necessary, one may do so. An example of this is “Levanon, Levanon Vesirion” when Mizmor LeDavid is chanted in Kabbalat Shabbat. In such a case there is no appearance of praying to two deities and the repetition of the word Levanon does not change the meaning of that particular verse. Summary: There is room to be lenient when repeating words in a prayer when a particular tune necessitates it.

There are certain situations in which one will find oneself outside of one’s home on Hanukkah at the time of the Menorah lighting, such as when one visits one’s relatives or goes to a hotel while on vacation. If one were to leave one’s home after lighting time, that is, Tzet HaKochavim, then one should light the Menorah at one’s home, wait thirty minutes and then one may extinguish the flame before leaving. If, however, one were to leave before the Tzet HaKochavim and spend the night elsewhere, then one’s destination is would be considered one’s “home” and one would light there. If one were to leave before Tzet HaKochavim but will only arrive the next day, such as if one were travelling by airplane, then since such a mode of transportation does not have the status of a home, then one would be exempt from the Mitzvah of lighting the Menorah that night. It should be mentioned that although the ideal time to light is at Tzet HaKochavim, if the husband will be returning home later than that time, it is a universal custom to wait until he arrives before lighting. Summary: Wherever one will be as of Tzet HaKochavim is considered one’s home with regards to lighting the Menorah. An airplane is not considered a home and therefore one would be exempt from lighting if one were flying. The Gemara (Shabbat 23b) explains that one who is careful regarding the Mitzvah of lighting the Menorah will be granted children who are Torah scholars. Furthermore, it is explained that Rabbi Yitzhak Sagi Nahor (son of the Raavad) inquired of Eliyahu HaNavi that many people are careful regarding the Hanukkah lights yet most people do not have scholarly children. Eliyahu HaNavi responded that it only refers to those who are meticulous regarding all the laws and intricacies of the Mitzvah of Hanukkah. Additionally, he explained that the Gemara’s blessing is four-fold: that the person himself would merit being a Torah scholar, would have children, would have male children and would have children who are Torah scholars themselves. The Rama (Orah Haim 673:1) says that the choicest way (“Mitzvah min HaMuvhar”) to light the Menorah is with olive oil since this is essence of the miracle of Hanukkah. He adds that if one does not have olive oil, one may use any oil or even wax candles, which produce a clean and clear light. Olive oil has been used by numerous communities for generations for Hanukkah and Rabbi David Sitbon (Ale Hadas) writes that this was the custom in North Africa as well. Fortunately nowadays, olive oil is both readily available and affordable, but there is a question as to what exactly constitutes olive oil. Some products labelled as olive oil are actually the oil extracted from olive seeds, and although one would certainly fulfill one’s obligation, this would not be Mitzvah min HaMuvhar. As such, the ideal product is cold pressed extra virgin olive oil as this is most similar to what was used in the Bet HaMikdash. Summary: Ideally one should use cold pressed extra virgin olive oil for the Hanukkah lights, but one fulfills one’s obligation with other oils and with wax candles.

The Gemara (Bava Batra 10a) relates that Rabbi Elazar would give a small sum of money to charity prior to praying since the verse (Tehilim 17:15) says “I will see Your face through charity.” In other words, prior to beholding Hashem’s Presence as it were, in prayer, it is a commendable act to give charity. Based on the principle there is a widespread custom to give charity during the Vayvarech David section of Pesuke Dezimra, specifically when reciting the words “Ve’ata Moshel Bakol” (lit. “and You rule over everything”). According to Kabbalah, one should first give two coins and then one single coin, although this does not preclude the giving of any amount in any denomination. Any form of giving is acceptable, whether it is directly to a needy person or into a Tzedaka box. If a Tzedaka box is not available the Kaf Hahaim (51:44) says that one may take money with one’s right hand (as should always be the case) and place it into one’s left hand and designate it for charity. Furthermore, on Shabbat when handling money is not permitted, or if one does not have any money on one’s person, one may have in mind to give a certain amount of money to charity at a later time. One may also loan a person money prior to praying and according to the Rambam (Hilchot Matanot La’evyonim, 10:7), a loan is the highest form of charity. Charity has the power to remove any spiritual barriers which would otherwise hinder the acceptance of one’s prayers and therefore, it is praiseworthy to give charity not only before Shaharit but before Minha and Arvit as well. Summary: The common custom to give charity during Vayvarech David in the morning, but it is commendable to do so before all prayers. Due to the importance of praying with the congregation, the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 52:1) gives guidelines to follow if one arrives at the synagogue and sees that the congregation has already reached the end of Pesuke Dezimra, or further. If there is not enough time for the above procedure, one should skip Hallelu Et Hashem Min Hashamayim. The Rama says that if time is very limited one may simply recite Baruch She’amar, Ashre and the Yishtabah. Finally, if one arrives and the congregation has already started the blessing of Yotzer, one should join them for Birkot Keriat Shema and the Amida, and then afterward, recite all of Pesuke Dezimra without a blessing. The Mishna Berura (M.B, O.H. 52:1) states that an angel transmitted to Rabbi Yosef Karo that, based on the Zohar and according to Kabbalah, one should never skip portions of Pesuke Dezimra and that there is significance to saying everything in order. Thus according to this opinion, if one arrives late, one should recite Pesuke Dezimra in its entirety, even it means that one will miss praying with the congregation. The Hacham Tzvi (§ 36) clarifies and says that the Zohar’s intention is only for one who will not be able to catch up to the congregation. One who could catch up, however, should follow the Shulhan Aruch’s guidelines. The common custom is for one to follow the Shulhan Aruch and not the Kabbalisitic approach. Rabbi Israel Algazi (Shalme Tzibbur) writes that if one is chronically late to the prayer, one is allowed to recite Pesuke Dezimra in its entirety since in such a case, one would otherwise never have the opportunity to recite it properly. As such, according to this opinion, the Shulhan Aruch’s ruling only applies to one who is late sporadically. Summary: If one arrives to the synagogue and the congregation has already started Pesuke Dezimra, one should follow the guidelines outlined in the Shulhan Aruch. As mentioned previously, the Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 51:1) writes that Pesuke Dezimra begins with the blessing of Baruch She’amar and ends with the blessing of Yishtbach. The Magen Avraham (M.A., O.H. 51) says that once one completes the blessing of Baruch She’amar, one is not permitted to make any interruptions during the entire Pesuke Dezimra. Nevertheless, the Magen Avraham continues, one is permitted to make an interruption, such as answering “Amen” to a fellow’s blessing, in the middle of Baruch She’amar itself or in the middle of Yishtabah itself. Regarding interruptions within Pesuke Dezimra, there is a prominent disagreement between Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and Rabbi Shalom Messas. Rabbi Shalom Messas (Tevuot Shamesh, Orah Haim, § 12) posits that within the blessing of Baruch She’amar itself, one would be able to make an interruption, especially in light of the fact that the source of the blessing is not from the Gemara but rather from the Geonim. However, he holds that during the actual Mizmorim of Pesuke Dezimra, one is only permitted to answer Kedusha, the first few words of Modim and the first five “Amens” of Kaddish. According to his view, one is not permitted to answer “Amen” to any other blessing or anything after the first five “Amens” of Kaddish. On the other hand, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (approbation to Tevuot Shamesh) disagrees and says that during Pesuke Dezimra, one may answer “Amen” to any blessing. He cites the HIDA (Kesher Gudal, § 7:34), who bases himself on the Arizal (Sha’ar Kavanot, pg 1), who follows this opinion. Furthermore, the Ben Ish Hai (Parashat Vayigash, § 10) and the Mishna Berura (M.B., O.H. 51:8) concur. This disagreement does not appear to be a matter of custom, but rather a novel opinion on the part of Rabbi Shalom Messas. As a matter of fact, in his correspondence with Rabbi Shalom Messas, Rabbi Baruch Avraham Toledano (not to be confused with the more well-known Rabbi [Raphael] Baruch Toledano), who was also from Meknes, disagrees with his approach. Another practical application is if one must uses the restroom during Pesuke Dezimra. Rabbi Ovadia Yosef (Yabia Omer, vol. IX, § 108:31) rules that one is permitted to recite “Asher Yatzar” during Pesuke Dezimra. The Kaf Hahaim (K.H., O.H. 51:28), the Haye Adam and Rabbi Ben Zion Abba Shaul (Or Lezion, vol. II, ch. 5, § 2), on the other hand, say that one should wait till after Yishtabah in order to recite it. As a general rule, one should try and wait until after Yishtabah to recite Asher Yatzar, but if one is concerned lest one forgets to recite it altogether, one may do so during Pesuke Dezimra. Summary: One may answer “Amen” to any blessing during Pesuke Dezimra, in addition to Kedusha and the beginning of Modim. If one must recite “Asher Yatzar”, one should try and wait till after Yishtabah, but if necessary, one may do so in the middle of Pesuke Dezimra.Live Broadcast: Can one answer “Amen”?

Does someone who’s not part of a Minyan have to answer the prayer?

Minyan: Where does one have to be located to count?

Kaddish: Direction & Minors

In which direction is Kaddish recited and can a child be part of a Minyan?

The Shulhan Aruch (O.H. 55:1), when discussing the laws of Kaddish, says that Kaddish, just like other holy acts (reciting “Barechu”, Kedusha, etc.) must be recited in the presence of ten adult men. It goes on (ibid:4) to reject the opinion of the Tosafot, who say that when a congregation is hard-pressed to find a tenth man, a minor as young as six years old who knows to Whom one is praying may be counted as the tenth person. The Tosafot say that in such a situation, the minor should hold a Humash in his hands, since its holiness elevates the status of the minor. The Rama (ibid.) writes that even while holding a Humash, a minor should not be counted as part of a Minyan, but that there are lenient opinions in urgent situations.May one repeat words when chanting a prayer?

Traveling on Chanuka

What if One Travels on Hanukkah?

Understandably, it would be worthy that one tries his utmost to avoid such a situation, thus avoiding nullifying this precious mitzvah.

There is an opinion that one would be able to light a flashlight on an airplane, but one should not utter the blessings in this case. Interestingly, Rabbi Shalom Schwadron (Shu”t Maharsham) writes that a train could have the status of a home since, especially in the past, people spend significant amount of time and sleep in the train. Furthermore, a soldier who is spending the night in the battlefield and does not have someone who could halachically light on his behalf, would be exempt from the Mitzvah.Chanuka Halachot

Which Olive Oil is Preferable?

Giving Tzedaka before Prayer

When should charity be given?

What if the congregation already started Pesuke Dezimra?

In the case where the congregation is nearing the end of Pesuke Dezimra, one who arrives late should recite Baruch She’amar, Ashre (Mizmor 145), Hellelu Et Hashem Min Hashamayim (Mizmor 148), Hallelu E-l Bekodsho (Mizmor 150) and finally Yishtabah. The Rama (ibid.) adds that if one sees that one has more time than originally thought, one should recite Hodu until the verse “Vehu Rahum”. One should then continue on with Birkot Keriat Shema and the Amida with the congregation.When is Mizmor Letoda Skipped?

In the times of the Bet Hamikdash, there existed a Thanksgiving offering which, in the words of Rashi (Vayikra 7:12), people would offer in gratitude of a personal mirage, and was known as Korban Toda. In the absence of the Bet Hamikdash, our Sages instituted as a substitute the recitation of Mizmor 100 (Mizmor Letoda) during Pesuke Dezimra. Since the laws of this offering stipulated that it was not brought on Shabbat or Yom Tov, the Rama (O.H. 51:9) says in the name of the Tur (O.H. 51), that this Mizmor is also not recited on these days. Furthermore, the offering was brought together with leavened bread, and therefore, this Mizmor is also not recited on the eve of Pesah, when Hametz is already forbidden. Finally, the Korban Toda was not offered on the eve of Yom Kippur since it would not be able to be consumed that night, when the fast had already begun, and thus, the Rama continues, Mizmor 100 is also not recited on that day.The Bet Yosef (O.H. 281) questions the logic of the aforementioned Tur by saying that the Mizmor is simply an expression of gratitude and does not necessarily need to parallel the laws of the actual Korban Toda. Indeed, Rabbi Baruch Toledano (Kitzur Shulhan Aruch, pg. 44) writes that the Moroccan custom was to refrain from reciting this psalm on the days listed above, and this is echoed in the Siddur Bet Oved. Rabbi Elazar Tobo (Pekudat Elazar), who emigrated to Israel from Morocco, writes that this was also the custom among the Sephardic community in Jerusalem, which included an established Moroccan communityThe Siddur Bet Oved cites an opinion from Rabbi Israel Saruk (Mahari Saruk), who says that since the Korban Toda was offered standing up, so too, Mizmor Letoda should be recited standing up. Nevertheless, the HIDA says that although it commemorates the Korban Toda, the Mizmor is not literally like the offering and therefore it may be recited sitting down, and this appears to be the common custom. Summary: The Moroccan custom is for Mizmor Letoda to be skipped on Shabbat, Yom Tov, Erev Pesah and Erev Yom Kippur. The original custom was for it to be skipped on Tisha Be’Av as well. Mizmor Letoda is recited sitting down. Interrupting Pesuke Dezimra

May one interrupt Pesuke Dezimra?

Sign up for the Daily Moroccan Halachot Email